×Fichiers du thème manquants :

themes/bootstrap3/squelettes/1col.tpl.html

themes/bootstrap3/styles/bootstrap.min.css

Le thème par défaut est donc utilisé.

themes/bootstrap3/squelettes/1col.tpl.html

themes/bootstrap3/styles/bootstrap.min.css

Le thème par défaut est donc utilisé.

112 Entrée de transition

Les bâtiments, et surtout les maisons, avec une transition gracieuse entre la rue et l'intérieur, sont plus tranquilles que ceux qui s'ouvrent directement sur la rue.

L'expérience de l'entrée dans un bâtiment influence la façon dont vous vous sentez à l'intérieur. Si la transition est trop abrupte, il n'y a pas de sentiment d'arrivée, et l'intérieur du bâtiment n'est pas un sanctuaire.

L'argument suivant peut aider à l'expliquer. Lorsque les gens sont dans la rue, ils adoptent un style de "comportement de rue". Lorsqu'ils entrent dans une maison, ils veulent naturellement se débarrasser de ce comportement de rue et s'installer complètement dans l'esprit plus intime propre à une maison. Mais il semble probable qu'ils ne puissent pas y parvenir, sauf s'il y a une transition de l'un à l'autre qui les aide à perdre le comportement de rue. La transition doit en effet détruire l'élan de fermeture, de tension et de "distance" qui est propre au comportement de rue, avant que les gens ne puissent se détendre complètement.

Les preuves proviennent du rapport de Robert Weiss et Serge Bouterline, Fairs, Exhibits, Pavillons, and their Audiences,Cambridge, Mass. 1962. Les auteurs ont remarqué que de nombreuses expositions ne parvenaient pas à "retenir" les gens ; les gens s'y installaient puis en repartaient en très peu de temps. Cependant, dans une exposition, les gens ont dû traverser un énorme tapis orange vif, très épais, en entrant. Dans ce cas, bien que l'exposition n'ait pas été meilleure que les autres, les gens sont restés. Les auteurs ont conclu que les gens étaient, en général, sous l'influence de leur propre "comportement dans la rue et dans la foule" et que, sous cette influence, ils ne pouvaient pas se détendre suffisamment pour entrer en contact avec les objets exposés. Mais le tapis lumineux leur présentait un contraste si fort lorsqu'ils entraient, qu'il brisait l'effet de leur comportement extérieur, en fait les "nettoyait", avec pour résultat qu'ils pouvaient ensuite être absorbés par l'exposition.

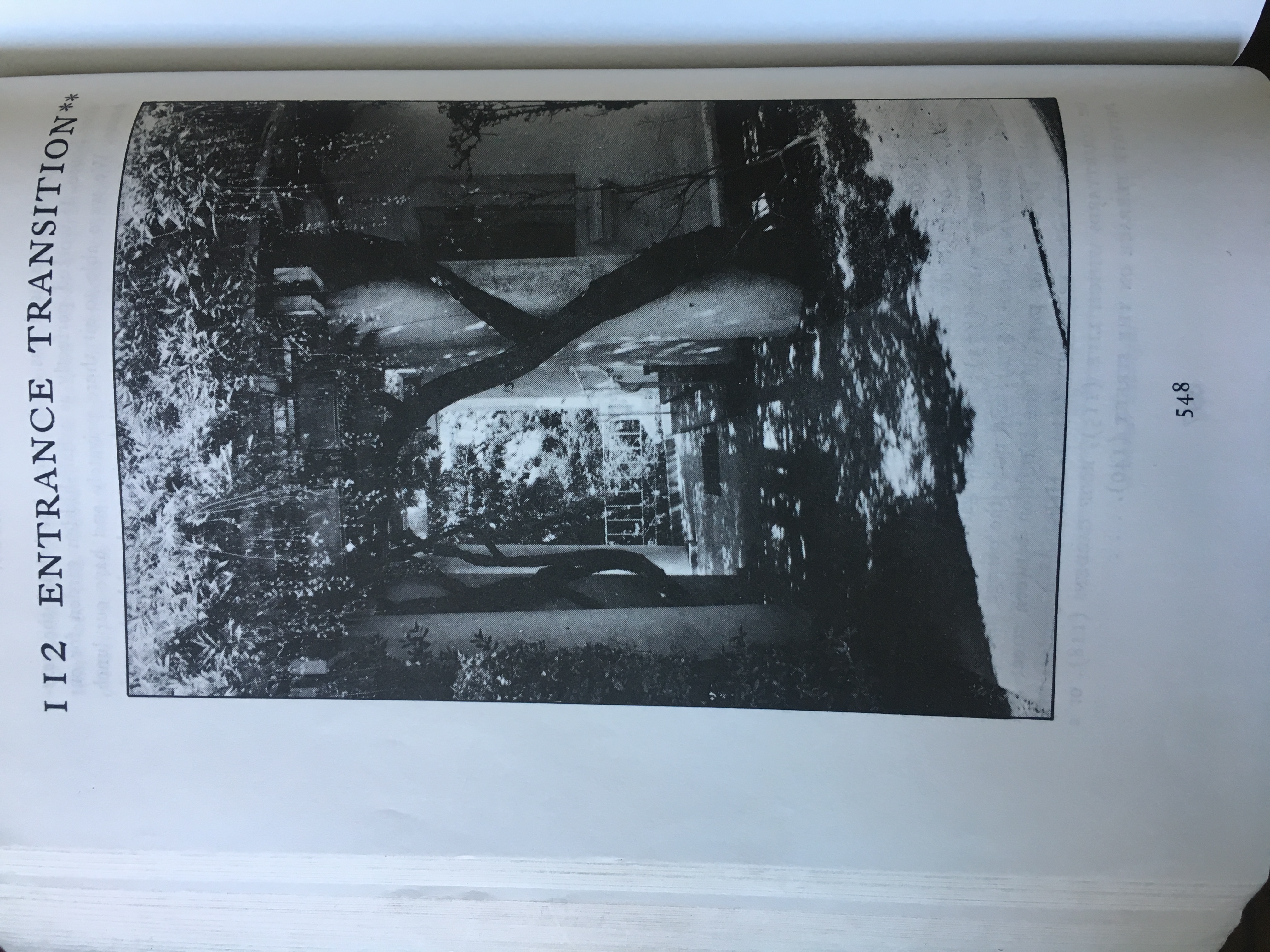

Michael Christiano, alors qu'il était étudiant à l'université de Californie, a fait l'expérience suivante. Il a montré aux gens des photographies et des dessins d'entrées de maisons avec des degrés de transition variables et leur a ensuite demandé laquelle d'entre elles était la plus "propre". Il a découvert que plus une entrée de maison présente de changements et de transitions, plus elle semble "ressembler à une maison". Et l'entrée qui a été jugée la plus agréable est celle qui est accessible par une longue galerie ouverte et abritée d'où l'on a une vue au loin.

Un autre argument permet d'expliquer l'importance de la transition : les gens veulent que leur maison, et surtout l'entrée, soit un domaine privé. Si la porte d'entrée est en retrait, et qu'il y a un espace de transition entre elle et la rue, ce domaine est bien établi. Cela expliquerait pourquoi les gens ne veulent souvent pas se passer d'une pelouse devant chez eux, même s'ils ne l'"utilisent" pas. Cyril Bird a constaté que 90 % des habitants d'un projet de logement ont déclaré que leurs jardins de devant, qui font environ 6 mètres de profondeur, étaient tout à fait corrects, voire trop petits - pourtant, seuls 15 % d'entre eux ont utilisé les jardins comme lieu de repos ("Réactions à Radburn : A Study of Radburn Type Housing, in Hemel Hempstead", thèse finale du RIBA, 1960).

Jusqu'à présent, nous avons surtout parlé des maisons. Mais nous pensons que ce schéma s'applique à une grande variété d'entrées. Il s'applique certainement à tous les logements, y compris les appartements, même s'il est généralement absent des appartements aujourd'hui. Il s'applique également aux bâtiments publics qui prospèrent grâce à un sentiment d'isolement du monde : une clinique, une bijouterie, une église, une bibliothèque publique. Elle ne s'applique pas aux bâtiments publics ou à tout autre bâtiment qui prospère grâce au fait d'être en continuité avec le monde public.

Comme vous le voyez dans ces exemples, il est possible d'effectuer la transition elle-même de nombreuses manières physiques différentes. Dans certains cas, par exemple, elle peut se faire juste à l'intérieur de la porte d'entrée - une sorte de cour d'entrée, menant à une autre porte ou ouverture qui se trouve plus définitivement à l'intérieur. Dans un autre cas, la transition peut être formée par un virage dans le chemin qui vous mène à travers une porte et qui frôle le fuchsia sur le chemin de la porte. Ou encore, vous pouvez créer une transition en changeant la texture du chemin, de sorte que vous quittiez le trottoir pour un chemin de gravier, puis montiez une ou deux marches et passez sous un treillis.

Dans tous ces cas, ce qui importe le plus est que la transition existe, en tant que lieu physique réel, entre l'extérieur et l'intérieur, et que la vue, les sons, la lumière et la surface sur lesquels vous marchez changent lorsque vous passez par ce lieu. Ce sont les changements physiques - et surtout le changement de point de vue - qui créent la transition psychologique dans votre esprit.

112 Entrance Transition

Buildings, and especially houses, with a graceful transition between the street and the inside, are more tranquil than those which open directly off the street.The experience of entering a building influences the way you feel inside the building. If the transition is too abrupt there is no feeling of arrival, and the inside of the building fails to be an sanctum.

The following argument may help to explain it. While people are on the street, they adopt a style of "street behavior." When they come into a house they naturally want to get rid of this street behavior and settle down completely into the more intimate spirit appropriate to a house. But it seems likely that they cannot do this unless there is a transition from one to the other which helps them to lose the street behavior. The transition must, in effect, destroy the momentum of the closedness, tension and "distance" which are appropriate to street behavior, before people can relax completely.

Evidence comes from the report by Robert Weiss and Serge Bouterline, Fairs, Exhibits, Pavilions, and their Audiences,Cambridge, Mass., 1962. The authors noticed that many exhibits failed to "hold" people; people drifted in and then drifted out again within a very short time. However, in one exhibit people had to cross a huge, deep-pile, bright orange carpet on the way in. In this case, though the exhibit was no better than other exhibits, people stayed. The authors concluded that people were, in general, under the influence of their own "street and crowd behavior," and that while under this influence could not relax enough to make contact with the exhibits. But the bright carpet presented them with such a strong contrast as they walked in, that it broke the effect of their outside behavior, in effect "wiped them clean," with the result that they could then get absorbed in the exhibit.

Michael Christiano, while a student at the University of California, made the following experiment. He showed people photographs and drawings of house entrances with varying degrees of transition and then asked them which of these had the most "houseness." He found that the more changes and transitions a house entrance has, the more it seems to be "houselike." And the entrance which was judged most houselike of all is one which is approached by a long open sheltered gallery from which there is a view into the distance.

There is another argument which helps to explain the importance of the transition: people want their house, and especially the entrance, to be a private domain. If the front door is set back, and there is a transition space between it and the street, this domain is well established. This would explain why people are often unwilling to go without a front lawn, even though they do not "use it." Cyril Bird found that 90 per cent of the inhabitants of a housing project said their front gardens, which were some 20 feet deep, were just right or even too small - yet only 15 per cent of them ever used the gardens as a place to sit. ("Reactions to Radburn: A Study of Radburn Type Housing, in Hemel Hempstead," RIBA final thesis, 1960.)

So far we have spoken mainly about houses. But we believe this pattern applies to a wide variety of entrances. It certainly applies to all dwellings including apartments even though it is usually missing from apartments today. It also applies to those public buildings which thrive on a sense of seclusion from the world: a clinic, a jewelry store, a church, a public library. It does not apply to public buildings or any buildings which thrive on the fact of being continuous with the public world.

As you see from these examples, it is possible to make the transition itself in many different physical ways. In some cases, for example, it may be just inside the front door - a kind of entry court, leading to another door or opening that is more definitely inside. In another case, the transition may be formed by a bend in the path that takes you through a gate and brushes past the fuchsia on the way to the door. Or again, you might create a transition by changing the texture of the path, so that you step off the sidewalk onto a gravel path and then up a step or two and under a trellis.

In all these cases, what matters most is that the transition exists, as an actual physical place, between the outside and the inside, and that the view, and sounds, and light, and surface which you walk on change as you pass through this place. It is the physical changes - and above all the change of view - which creates the psychological transition in your mind.

Se connecter pour commenter.

Commentaires