×Fichiers du thème manquants :

themes/bootstrap3/squelettes/1col.tpl.html

themes/bootstrap3/styles/bootstrap.min.css

Le thème par défaut est donc utilisé.

themes/bootstrap3/squelettes/1col.tpl.html

themes/bootstrap3/styles/bootstrap.min.css

Le thème par défaut est donc utilisé.

120 Chemins à étapes

La disposition des sentiers ne semblera juste et agréable que lorsqu’elle est compatible avec le processus de marche. Et le processus de marche est beaucoup plus subtil qu’on pourrait l’imaginer.

Globalement, il y a trois processus complémentaires :

1. [Un chemin vers un objectif] En marchant sur un sentier, vous parcourez des yeux le paysage à la recherche de destinations intermédiaires - les repères les plus éloignés du chemin parcouru. Vous essayez, plus ou moins, de marcher en ligne droite vers ces repères. Cela a naturellement pour effet de couper des coins et de prendre des chemins «en diagonale», car ce sont ceux qui forment souvent des lignes droites entre votre position actuelle et le repère que vous voulez atteindre.

2. [Séries d'objectifs] Ces destinations intermédiaires changent constamment. Plus vous marchez, plus vous pouvez voir au coin de la rue. Si vous marchez toujours tout droit vers ce point le plus éloigné et que le point le plus éloigné change constamment, vous vous déplacerez en fait dans une courbe lente, comme un missile qui suit une cible en mouvement.

3- [Le chemin le plus réaliste] Puisque vous ne voulez pas changer de direction pendant que vous marchez et ne voulez pas passer tout votre temps à re-calculer le meilleur déplacement, vous organisez votre processus de marche de telle manière que vous choisissez un «objectif» temporaire - un repère clairement visible - qui est plus ou moins dans la direction que vous voulez prendre. Puis vous marchez en ligne droite vers elle pendant une centaine de mètres, puis, comme vous vous approchez, choisissez un autre but, une fois de plus une centaine de mètres plus loin, et marchez vers elle [...] Vous faites cela pour qu’entre les deux, vous puissiez parler, penser, rêver, sentir le printemps, sans avoir à penser à la direction à prendre chaque minute.

La bonne organisation des chemins à suivre serait celle avec suffisamment d’objectifs intermédiaires, pour rendre ce processus réalisable. S’il n’y a pas assez d’objectifs intermédiaires, le processus de marche devient plus ardu et consomme une énergie émotionnelle inutile (chercher la bonne direction, avoir peur de se tromper de route etc...).

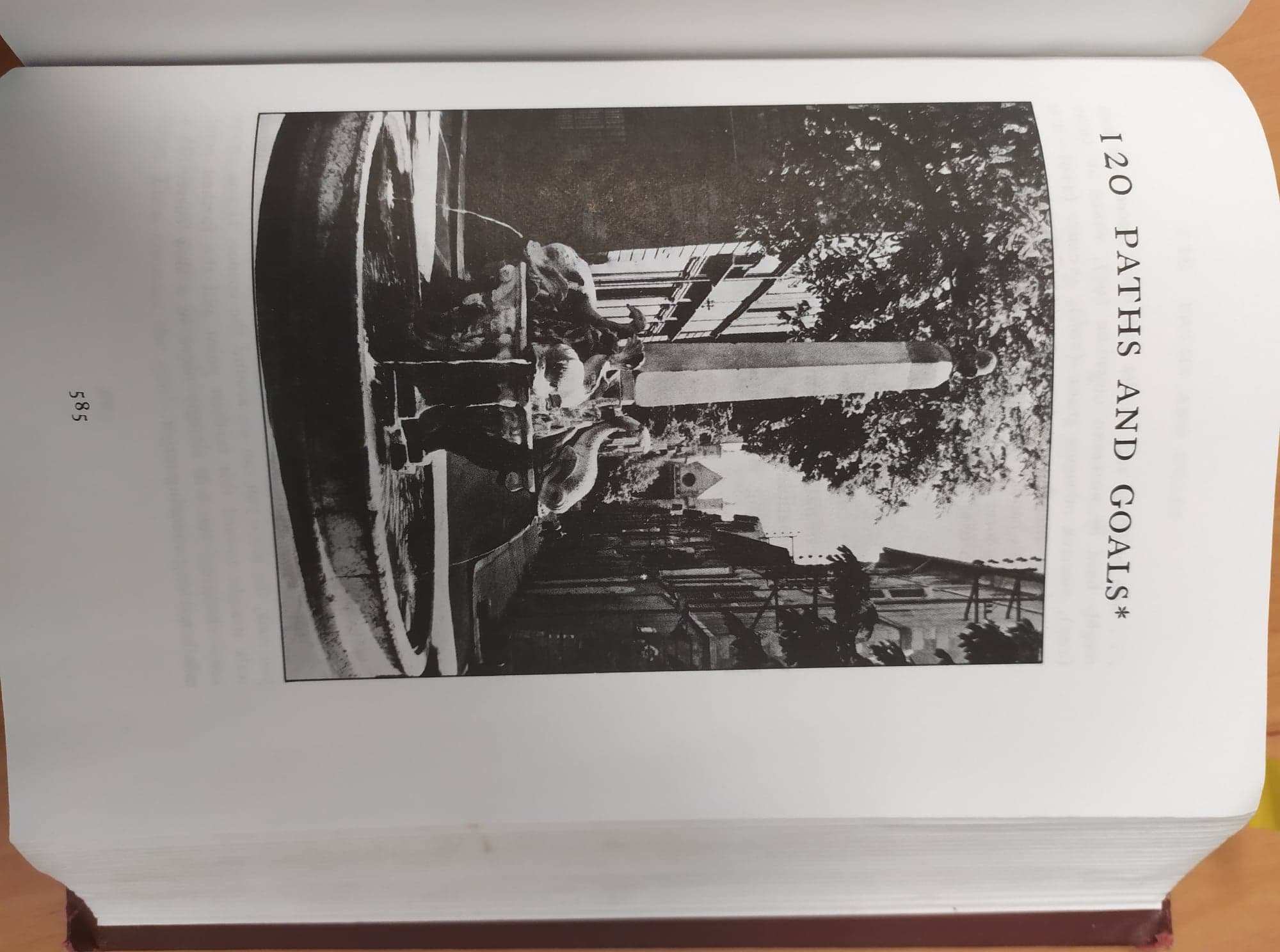

120 Paths and Goals

The layout of paths will seem right and comfortable only when it is compatible with the process of walking. And the process of walking is far more subtle than one might imagine.Essentially there are three complementary processes:

1. [Path to a goal] As you walk along you scan the landscape for intermediate destinations - the furthest points along the path which you can see. You try, more or less, to walk in a straight line toward these points. This naturally has the effect that you will cut corners and take "diagonal" paths, since these are the ones which often form straight lines between your present position and the point which you are making for.

2. [Series of goals] These intermediate destinations keep changing. The further you walk, the more you can see around the corner. If you always walk straight toward this furthest point and the furthest point keeps changing, you will actually move in a slow curve, like a missile tracking a moving target.

3- [The actual Path] Since you do not want to keep changing direction while you walk and do not want to spend your whole time re-calculating your best direction of travel, you arrange your walking process in such a way that you pick a temporary "goal" - some clearly visible landmark - which is more or less in the direction you want to take and then walk in a straight line toward it for a hundred yards, then, as you get close, pick another new goal, once more a hundred yards further on, and walk toward it. . . . You do this so that in between, you can talk, think, daydream, smell the spring, without having to think about your walking direction every minute.

In the diagram above a person begins at A and heads for point E. Along the way, his intermediate goals are points B, C, and D. Since he is trying to walk in a roughly straight line toward E, his intermediate goal changes from B to C, as soon as C is visible; and from C to D, as soon as D is visible.

The proper arrangements of paths is one with enough intermediate goals, to make this process workable. If there aren't enough intermediate goals, the process of walking becomes more difficult, and consumes unnecessary emotional energy.

Se connecter pour commenter.

Commentaires