×Fichiers du thème manquants :

themes/bootstrap3/squelettes/1col.tpl.html

themes/bootstrap3/styles/bootstrap.min.css

Le thème par défaut est donc utilisé.

themes/bootstrap3/squelettes/1col.tpl.html

themes/bootstrap3/styles/bootstrap.min.css

Le thème par défaut est donc utilisé.

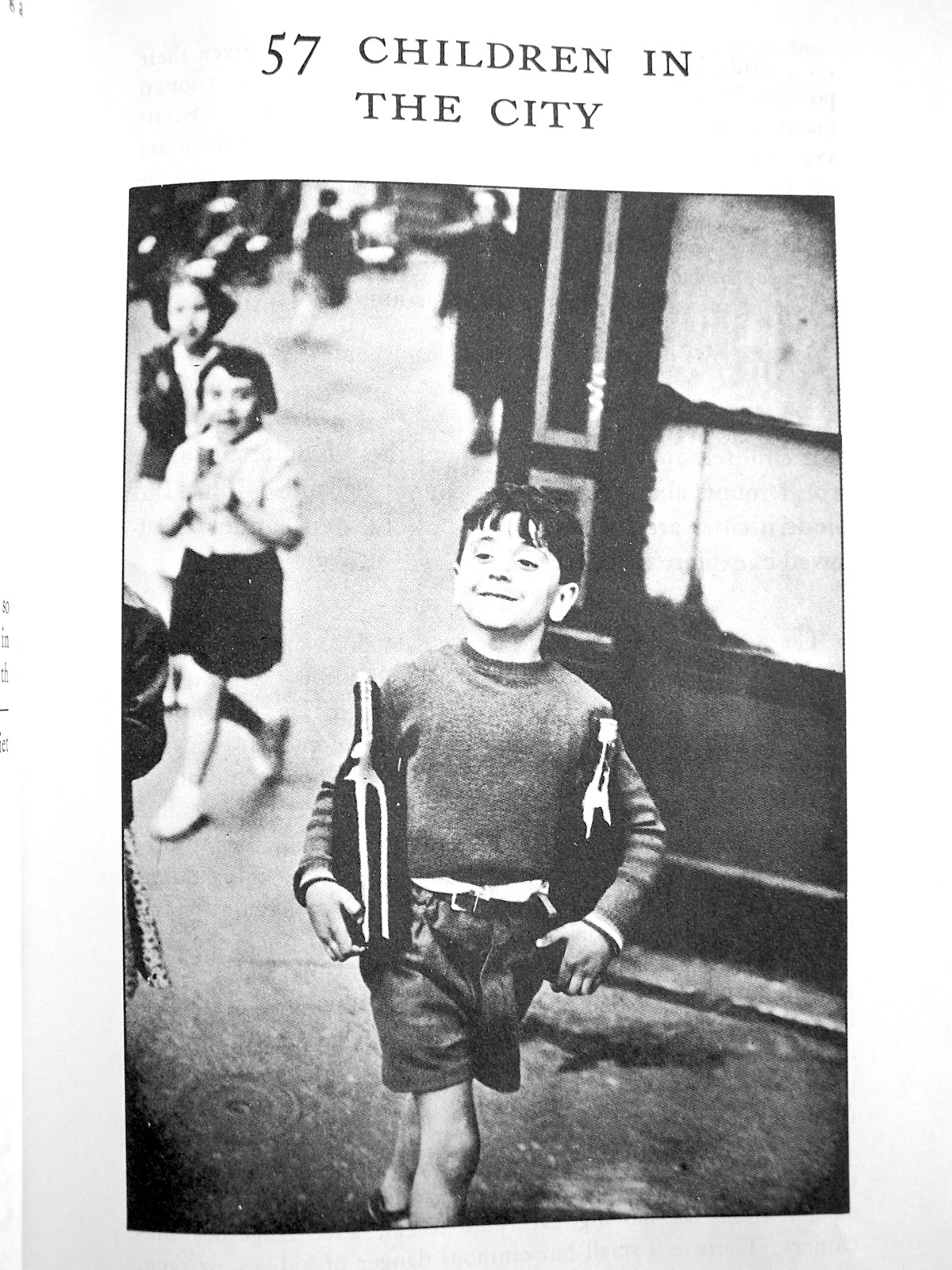

57 Les enfants dans la ville

Si les enfants ne sont pas capables d'explorer tout le monde adulte qui les entoure, ils ne peuvent pas devenir adultes. Mais les villes modernes sont si dangereuses que les enfants ne peuvent pas être autorisés à les explorer librement.

La nécessité pour les enfants d'avoir accès au monde des adultes est tellement évidente qu'elle va de soi. Les adultes transmettent leur éthique et leur mode de vie aux enfants par leurs actions, et non par leurs déclarations. Les enfants apprennent en faisant et en copiant. Si l'éducation de l'enfant se limite à l'école et à la maison, et si toutes les vastes entreprises d'une ville moderne sont mystérieuses et inaccessibles, il est impossible pour l'enfant de découvrir ce que signifie réellement être un adulte et il lui est certainement impossible de le copier en faisant.

Le problème semble presque insoluble. Mais nous pensons qu'il peut être résolu au moins en partie en agrandissant les quartiers des villes où les jeunes enfants peuvent être laissés seuls à errer et en essayant de faire en sorte que ces ceintures pour enfants protégées soient si étendues et si vastes qu'elles touchent toute la gamme des activités et des modes de vie des adultes.

Nous imaginons une piste cyclable pour enfants soigneusement aménagée, dans le cadre du réseau plus vaste des pistes cyclables. La piste passe devant et à travers des parties intéressantes de la ville ; et elle est relativement sûre. Elle fait partie du système global et est donc utilisée par tout le monde. Il ne s'agit pas d'une "balade" spéciale pour les enfants - qui serait immédiatement évitée par les jeunes aventuriers - mais elle possède une voie spéciale, et peut-être est-elle spécialement colorée.

Le chemin est toujours une piste cyclable ; il ne passe jamais à côté des voitures. Là où elle croise la circulation, il y a des feux ou des ponts. Il y a beaucoup de maisons et de magasins le long de la piste - les adultes sont à proximité, surtout les personnes âgées qui aiment passer une heure par jour assises le long de cette piste, elles-mêmes roulant le long de la boucle, regardant les enfants du coin de l'œil.

Et surtout, la grande beauté de ce chemin est qu'il passe le long et même à travers les fonctions et les parties d'une ville qui sont normalement hors de portée : le lieu où les journaux sont imprimés, le lieu où le lait arrive de la campagne et est mis en bouteille, la jetée, le garage où les gens font les portes et les fenêtres, l'allée derrière la rangée de restaurants, le cimetière.

57 Children in the city

If children are not able to explore the whole of the adult world round about them, they cannot become adults. But modern cities are so dangerous that children cannot be allowed to explore them freely.The need for children to have access to the world of adults is so obvious that it goes without saying. The adults transmit their ethos and their way of life to children through their actions, not through statements. Children learn by doing and by copying. If the child's education is limited to school and home, and all the vast undertakings of a modern city are mysterious and inaccessible, it is impossible for the child to find out what it really means to be an adult and impossible, certainly, for him to copy it by doing.

This separation between the child's world and the adult world is unknown among animals and unknown in traditional societies. In simple villages, children spend their days side by side with farmers in the fields, side by side with people who are building houses, side by side, in fact, with all the daily actions of the men and women round about them: making pottery, counting money, curing the sick, praying to God, grinding corn, arguing about the future of the village.

But in the city, life is so enormous and so dangerous, that children can't be left alone to roam around. There is constant danger from fast-moving cars and trucks, and dangerous machinery. There is a small but ominous danger of kidnap, or rape, or assault. And, for the smallest children, there is the simple danger of getting lost. A small child just doesn't know enough to find his way around a city.

The problem seems nearly insoluble. But we believe it can be at least partly solved by enlarging those parts of cities where small children can be left to roam, alone, and by trying to make sure that these protected children's belts are so widespread and so far-reaching that they touch the full variety of adult activities and ways of life.

We imagine a carefully developed childrens' bicycle path, within the larger network of bike paths. The path goes past and through interesting parts of the city; and it is relatively safe. It s part of the overall system and therefore used by everyone. It s not a special children's "ride" -which would immediately be shunned by the adventurous young-but it does have a special lane, and perhaps it is specially colored.

The path is always a bike path; it never runs beside cars. Where it crosses traffic there are lights or bridges. There are many homes and shops along the path - adults are nearby, especially the old enjoy spending an hour a day sitting along this path, themselves riding along the loop, watching the kids out of the corner of one eye.

And most important, the great beauty of this path is that it passes along and even through those functions and parts of a town which are normally out of reach: the place where newspapers are printed, the place where milk arrives from the countryside and is bottled, the pier, the garage where people make doors and windows, the alley behind restaurant row, the cemetery.

Se connecter pour commenter.

Commentaires